The Complex Relationship Between -id and -or

The English language, notorious for its pervasive irregularities and apparent inconsistencies, includes a trend that, when applied to certain word forms, leads to some curious results. The trend to which I refer is the relationship of adjectives ending in –id to corresponding nouns ending in –or. This trend is seen exclusively amongst words with Latin roots. Here is a table containing some examples of such adjectives:

It should be noted that stupor is not the exact noun form of stupid, which is actually stupidity. And, while stupidity and stupor convey different nuances, there is enough overlap in their definitions to make the noun-verb connection apparent. There are, however, just as many adjectives ending in –id with corresponding nouns that do not follow this trend. These nouns tend to end in the more common –idity and –ness. Here are some examples:

This second list acts as a reminder of just how irregular English conjugation is. A much more interesting list, however, includes adjectives ending in –id which, if run through the –id → –or conjugation mechanism, produce curious results. The following list includes the grammatically correct noun forms of these adjectives, as well as a list of nouns ending in –or which could possibly share some etymological relationship to the corresponding adjectives:

List 3: Adjectives with corresponding nouns that do not follow the -id --> -or pattern, but for which there exist other nouns, whether related to the initial adjectives or not, that do fall into the pattern

This is the list of most interest because, unlike the others, it does not merely consist of examples and counterexamples of the –id –> –or pattern. It presents us with an opportunity to explore the relationships between certain adjectives and the nouns that, coincidentally or not, are spelled and pronounced so as to fit the pattern established by the first list. Could the italicized nouns give us a glimpse into arcane uses of these adjectives? It requires no stretch of the imagination to see how the meaning of valid could be related to that of valor, the actions of a person possessing the Greek quality of valor being considered valid by the societal norms of the time. Similarly, it is easy to see how a relationship between liquid and liquor could exist somewhere in the recesses of word origins. But what of vapid → vapor and humid → humor?

While the word vapid is most commonly used as a synonym for insipid or lifeless, the Oxford English Dictionary reveals that, in the 17th century, vapid was used to mean, “Of a damp or steamy character; dank, vaporous.” Here, it seems, lies the –id → –or connection between vapid and vapor, an outdated relationship betrayed by the modern word forms in which it no doubt resulted. To unearth the connection between humid and humor also requires the pondering of a definition that has fallen out of use. The Oxford English Dictionary lists, among its definitions of humid, several relevant usages that haven’t been common for centuries. While the primary definition is, “Slightly wet as with steam, suspended vapor, or most; moist, damp.”, several historical uses of the word include, “In medieval physiology, said of elements, humours…Said of a chemical process in which liquid is used…Of diseases: Marked by a moist discharge.” This conception of humor (a reference to the Four Humours or Temperaments, medical notions that hearken back to ancient Egypt and Greece), here referring to wetness, gave rise to our modern notion of the word, currently used to mean, “Mood natural to one’s temperament…” and, “The faculty of perceiving what is ludicrous or amusing, or of expressing it in speech, writing, or other composition.” To uncover the relationship requires a look at classical medicine and its assumptions regarding the functioning of the human body.

A chart outlining the relationship of the four humours (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm) with the physical body and its personality traits

According to this conception of human health, one whose composition is characterized by moistness walks the line between sanguine and phlegmatic. Those with sanguine temperaments were ascribed the traits of extroversion and sociability, while phlegmatics were considered kind and relaxed. It does not require a far leap to bridge the gap between the ancient notion of physiological humidity and our contemporary use of the word humorous to suggest a jovial and comedic personality. The following image shows how moisture was associated with a sanguine-phlegmatic temperament:

Having deciphered the aforementioned relationships through a bit of etymological archaeology, it seems necessary to address one final list of words. Here is a list of common nouns ending in –or with corresponding adjectives that seem to follow no discernable pattern:

List 4: Nouns ending in -or with corresponding adjectives that do not follow the -id --> -or pattern

While this last list does not present any immediately obvious clues regarding outdated word usage, it leads to another interesting line of inquiry. Why is there no adjective form of temblor in the English language, whether modern or arcane? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the world temblor, synonymous with earthquake, is an Americanism not seen in print earlier than 1876. Since the word is so young and is not commonly used, perhaps it simply never had the chance to sprout related adjectives. Perchance this could lead to the temblorous conclusion that English word forms only emerge if they are necessary, and do not merely arise out of grammatical convention.

Some Further Reading:

An article about Greek virtue ethics

A look at the classical conception of the four bodily humours

An exhaustive list of –id adjectives that makes special note of vapor and humor. Oddly, this list suggests that valor and valid are unrelated, while glossing over the relationship between humor and humid

Thursday, the Day of Thor

Irrational Geographic is so often concerned with notions ancient and arcane that, in this novel entry, I’ve decided to take an opposite approach. Today is Thursday, the 6th of August. So as to remain as temporally present and as commonplace as possible, I have decided to make an inquiry into Thursday itself. One seventh of our shared existence is spent inside of this designated period of time, so its origins, both as an entity and as a word, are of undeniable interest.

An artistic representation of the months and seasons of the modern Gregorian calendar, here juxtaposed with the ancient Hebrew calendar.

Thursday is designated the fifth day of the week according to the Gregorian calendar, which is currently the Western standard for the temporal demarcation of the year (There are, of course, other calendrical systems currently in use, including the Jewish and Hindu calendars, and that of the Nigerian Igbo with their curious four-day week). This is only the case due to the fact that Sunday is widely designated as the week’s first day, an honor bestowed upon the day, named after the year-defining sun (from the Old English word Sunnendaeg, “Day of the sun”), by Judeo-Christian calendrical tradition. Some nations including The United Kingdom, on the other hand, still consider Sunday to be the week’s seventh day, making Thursday the fourth. The Chinese word for Thursday, in fact, means fourth. The ancient Greeks and Romans would have taken issue with this, however, each designating their equivalent of Sunday as the week’s first day, associating it with supreme divinity.

The legendary Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, depicted Helios, the Greek sun god, for whom the first day of the week was named.

Despite the fact that Thursday sits on the opposite side of the week from Sunday, its namesake is certainly a source of great historical power and significance. Its moniker originates in a culture very different than that of Sunday. Thursday takes its name from Thor, simultaneously the ancient Norse god of thunder and Germanic god of protection.

”Thor’s Battle Against the Giants” by Swedish painter Marten Eskil Winge, 1872.

One of the oldest recorded deities of Scandinavian polytheistic culture, Thor (also referred to as Donor in some Germanic linguistic traditions) served as a symbol of Pagan resistance and cultural pride in the face of the monotheistic Christian encroachment upon Scandenavia beginning in the 8th century. Perhaps the fact that remnants of Thor grace our modern calendars (Thursday having taken the place of Dies Iovis, the ancient Latin “Day of Jupiter”) suggests that this resistance was never fully quelled despite the fact that, by the 12th century, Christianity had all but beaten Paganism out of the region.

A Medieval map of Scandinavia.

Like the evergreen tree decorated with candles and ribbons displayed during the Christmas celebration, the prominent inclusion of Thor’s name in a predominantly Judeo-Christian calendar is an instance of the hybridization of Pagan and monotheistic traditions that has survived into modern times. While the Christian crusaders of the Middle Ages may have aimed to bend the world to their will, they themselves received some cultural battle scars that are still visible today. Our word for Thursday is just such a scar, scratched approximately fifty two times across the face of every modern Western calendar.

Some Further Reading:

A look at the Igbo calendar as it relates to the notion of a spiritual cosmic order

A simple breakdown of the Hindu calendar

A tool that allows for the conversion of dates between the Gregorian and Jewish calendars

An essay that discusses the origins of the Christmas tree and its Pagan connections

A Wikipedia entry including some excellent charts comparing day nomenclature cross-culturally

The Lost Panacea of Silphium

Native to the ancient Greek colony of Cyrene (located in modern day Libya), Silphium (also known as laser) is an extinct plant that, in its heyday, was one of the most treasured medicinal resources of the ancient world. Employed by cultures all around the Mediterranean, Silphium was used as a spice, a cure-all medicinal remedy, a form of birth control, and an agent for pregnancy abortion. Famed scholars ranging from Pliny the Elder to Herodotus to Theophrastus all wrote of Silphium’s legendary potency. Despite its widespread popularity, Silphium allegedly refused to grow anywhere aside from Cyrene. The colony became so closely identified with the plant that it appears on the settlement’s coins.

Native to the ancient Greek colony of Cyrene (located in modern day Libya), Silphium (also known as laser) is an extinct plant that, in its heyday, was one of the most treasured medicinal resources of the ancient world. Employed by cultures all around the Mediterranean, Silphium was used as a spice, a cure-all medicinal remedy, a form of birth control, and an agent for pregnancy abortion. Famed scholars ranging from Pliny the Elder to Herodotus to Theophrastus all wrote of Silphium’s legendary potency. Despite its widespread popularity, Silphium allegedly refused to grow anywhere aside from Cyrene. The colony became so closely identified with the plant that it appears on the settlement’s coins.

Silphium, here seen on Cyrene's coins, was the colony's chief export. The plant was notoriously resistant to cultivation, and is believed to have been harvested to extinction within the first few centuries AD.

Silphium was so strongly desired by various ancient civilizations that it was, at times, valued above currency. With some Romans contending that the plant was a gift from the god Apollo, its extinction was considered a great tragedy. Pliny even wrote that the last known Silphium plant was given to the Roman Emperor Nero himself.

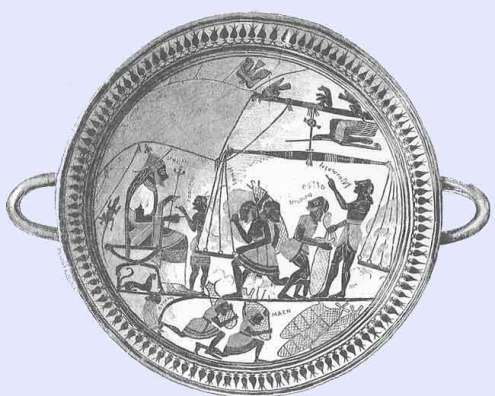

An artifact from the 6th century believed to depict King Arcesilaus II of Cyrene overseeing the weighing of Silphium.

The Egyptians shared the Romans’ veneration of the plant, associating its with human love and sexuality. The Egyptian glyph signifying the heart portion of the soul, in fact, may have been meant to picture the seed of the Silphium plant. This character, known to the Egyptians as Ib, is likely the origin of our modern heart symbol.

Here is an ancient Cyrene coin bearing the image of a Silphium seed. Its likeness both to the Egyptian Ib and to the modern heart symbol is striking.

While the world has been without Silphium and its powers for well over a millennium, our modern culture still bears its mark. Every time a love-dazed youth carves a heart into a tree or inserts a whimsical, heart-shaped emoticon into an online conversation, the plant that once commanded a king’s ransom is winking at us from the ghostly recesses of the Earth’s past. Like the Dodo bird that gave us an insult implying stupidity or the dinosaur that inhabits every child’s imagination, Silphium’s potency is strong enough to overcome the silencing power of extinction itself.

Some Further Reading:

Some information about Silphium’s possible use as birth control and an abortifacient

An article entitled “Abortion in the Ancient and Premodern World”

An article about ancient methods of measurement, including brief mention of Silphium from Cyrene

An essay addressing the five parts of the Egyptian soul, including Ib